by C.L. Michel

Cultivating Curiosity

Talking about prison is taboo—Canadian society deals with it far less than is common in other jurisdictions (eg., the United States). Most people in Canada don’t know anything about how the prison system works or what conditions in it are like if they or a loved one haven’t experienced it.

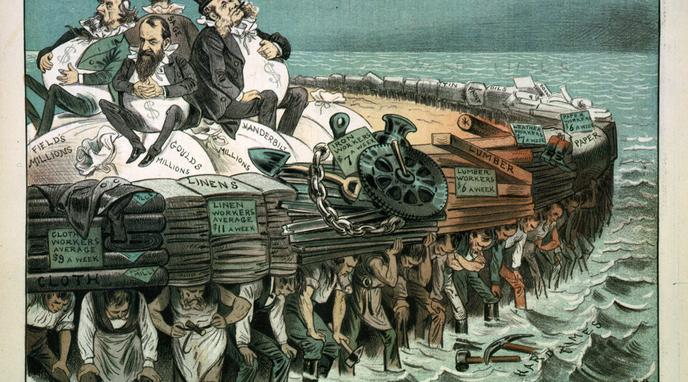

One reason for this is that prison produces silence. The voices of prisoners are cut off from the world, and what happens inside prisons only makes the news in the most extreme cases. This lack of attention is problematic because the prison system is central to how many different forms of oppression reproduce themselves. For instance, it maintains class society and economic exploitation. It is a tool of racist and colonial violence that keeps whole communities down, and it produces gendered forms of trauma on a mass scale.

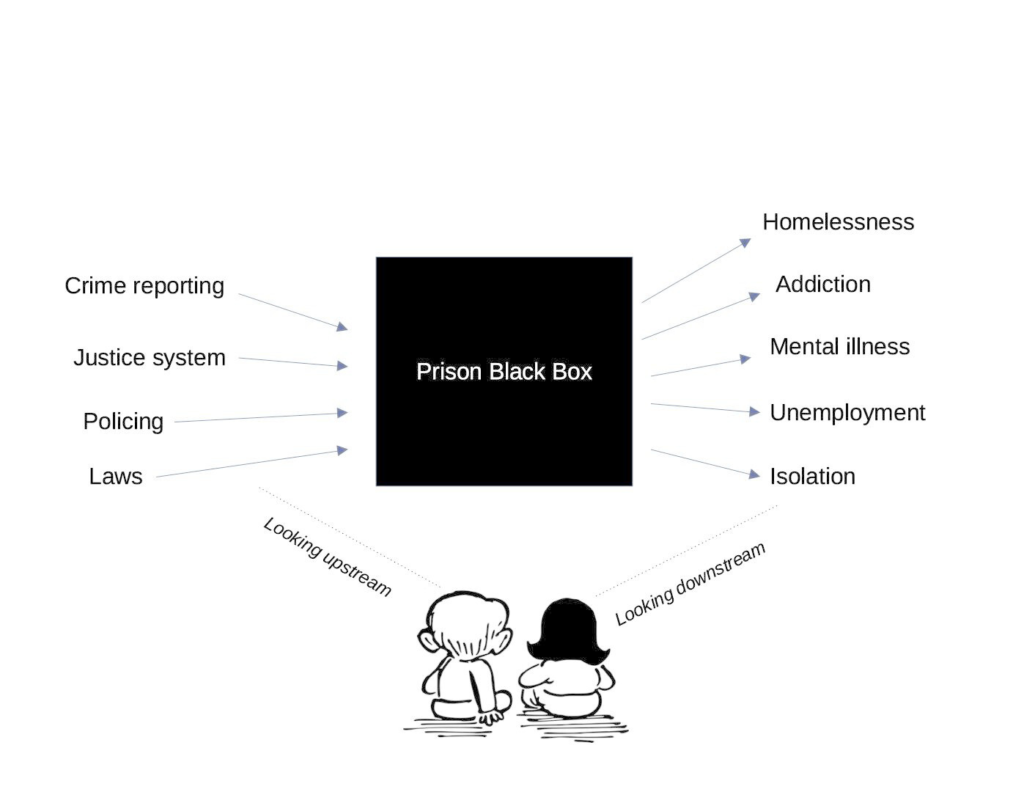

Prison functions like a black box. We can see what happens prior to entering the prison system in terms of crime, policing, and the justice system, and we can see the negative outcomes of the prison system once people leave, such as poverty, homelessness, and social exclusion, but the space in between is opaque—we can’t see the conditions inside prisons that produce these outcomes.

If we want to find solutions to complex problems like homelessness, we need to cultivate some curiosity about people’s experiences with systems we might not normally think about, like prison.

Types of Prisons in Canada

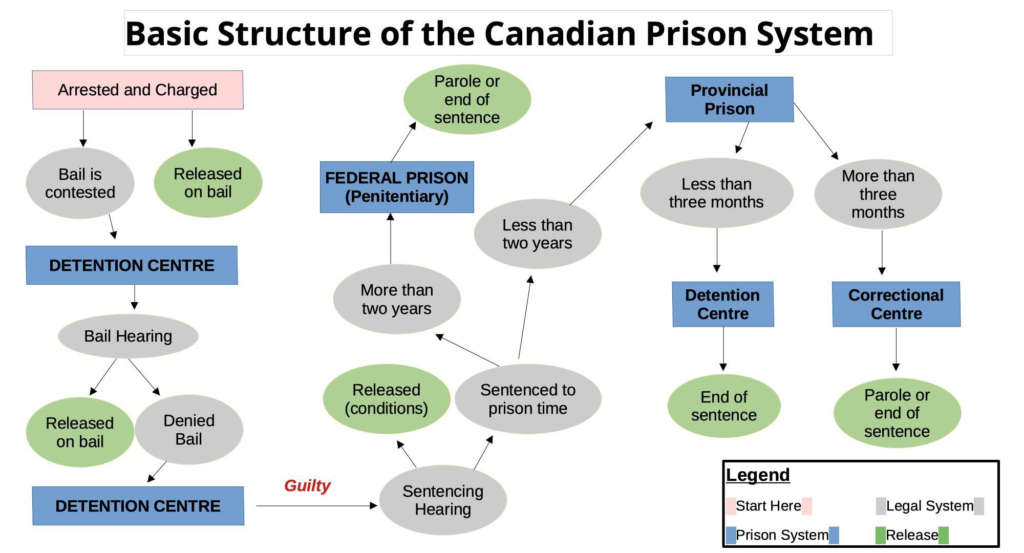

The various prisons in Canada are separated into two types: federal and provincial. Federal prisons, also known as penitentiaries, are where prisoners who are sentenced to over two years are sent. Although only about a third of all prisoners are in federal prison, it is what people think of on the rare occasions that they think about prison in Canada.

The remaining two thirds of prisoners are in provincial prisons. People sentenced to less than two years, those who have been denied bail, and an increasing number of immigration detainees are in provincial prisons. All federal prisoners have also spent time in a provincial prison, and the majority of prisoners will do all their time there. Despite this, they receive far less attention than federal prisons. In provincial prisons there is less programming, less oversight, and fewer organizations that provide support. The conditions inside these prisons are far, far worse.

In Ontario, the Ministry of the Solicitor General operates 25 adult prisons that hold around 7,500 prisoners on any given day, with an average period of incarceration of 45 days (almost 150,000 people are admitted into provincial prisons across Canada in any given year).

Many provinces subdivide provincial prisons into other administrative categories. For the purpose of this blog, we will be focusing on adult prisons in Ontario, but there are also youth prisons and mental health prisons. There are two kinds of adult provincial prisons in Ontario: detention centres (DCs), for those who have been denied bail or sentenced to less than three months, and correctional centres, for those who have been sentenced to between three months and two years.

In many provinces (eg., Ontario, Alberta, and Nova Scotia), about 70% of prisoners in provincial prisons are on “remand,” meaning they are only locked up because they were denied bail. This means that about half of all prisoners in Canada are on remand. This is a significantly higher proportion than in the United States, and it has been getting worse with time.

Since most of Canada’s prisoners are in remand, the conditions they face are crucial to understanding the prison system as a whole and the way it contributes to homelessness.

Conditions for Remand Prisoners in Ontario

Prisoners who have been denied bail are held in the harshest conditions in the prison system. All of Ontario’s DCs are considered maximum security, meaning they face the most restrictions on their movements, what they can have access to, and possibilities for programming.

Detention centres are very crowded. Cells built for one or two prisoners routinely hold three, with one person sleeping on a mattress on the floor. There are frequent lockdowns, which is when prisoners are confined to their cells except for half an hour every second day. Combine these two factors and you have three prisoners held together in a space the size of a bathroom stall for days at a time without even enough room to stand up and move around. This obviously aggravates physical and mental health conditions.

There are almost no programs in DCs, and there is very limited access to books. Visits are short (two 20-minute visits a week) and are frequently cancelled without notice. Although prisoners are entitled to 20 minutes of fresh air every day, they may only get “yard time” a couple of times a month.

Detention centres are also very violent. Since everyone in a DC is in pre-trial and the average stay is short, there is a high turnover with lots of coming and going, making hierarchies unstable. The needs of those living in a DC for short periods may conflict with those of prisoners there for years, and the overcrowded conditions with no privacy result in high stress levels.

Guards are also able to brutalize prisoners with near impunity. While a report from the Ontario ombudsman denounced the use of force by guards and the guards’ code of silence that interferes with investigations, this report was not enough to stop this violence from continuing.

When you add in the overdose crisis and an inadequate medical system to the previously mentioned factors, the result is that 29 people died inside of Ontario’s provincial prisons in 2021. From previous years’ statistics compiled by Reuters, 85% of all deaths in Ontario’s provincial prison are people in remand custody, meaning those in detention centres are dying at a disproportionate rate.

Although prison harms everyone it touches, it does not do this in the same way to everyone. Prison functions on the basis of separation, firstly by cutting people off from society, then by sorting them to expose them to different forms of harm. The administrative differences described above are one way of sorting people. Another important way the prison system does this is by gender or sex.

Gendered Harm

All prisoners are labelled as either male or female depending on the institution’s best guess of their sex at birth, and so there are two gendered forms of incarceration known as men’s and women’s prison. There is a lot to say about how the Ontario prison system deals with trans identity, but for the purposes of this blog, it is enough to know that almost all trans people go to women’s prison. Women’s prison can be thought of as a prison for people who would be at risk of sexual violence if all prisoners were just lumped together.

Officially, there should be little difference between men’s and women’s prisons, and the conditions are generally the same. However, it is worth reflecting on how identical treatment within an unequal society produces drastically different results.

To give a quick example, the food in men and women’s prison is exactly the same. In men’s prison, this is mostly felt to be insufficient, in part because working out is a big part of prisoner culture. Men prisoners are often released stronger and fitter than when they went in. In women’s prisons, exercise is discouraged both by prisoner culture and by the guards. Women prisoners often experience rapid weight gain and a general decrease in fitness due to the enforced immobility.

In this example and in so many others, sorting people by gender means the prison system is involved in reproducing negative gender dynamics. Many conditions faced by women prisoners compound common forms of gender-based trauma, such as:

- Frequent strip searches

- Round the clock surveillance by male guards

- The absence of privacy

- Losing custody over children

- Losing housing

After release, feminized professions tend to care more about criminal records than many male-dominated ones: consider customer service vs. construction or childcare vs. trucking. This results in women experiencing more exclusion from the job market upon release, contributing to cycles of dependence and victimization.

Similarly, the intense violence of men’s prison is tied to a macho prisoner culture steeped in homophobia and misogyny. This culture is then exported back out into communities by former prisoners. Both gendered experiences leave people more likely to commit future criminalized acts and end up back in prison.

Why Does this Matter to the Homelessness Sector?

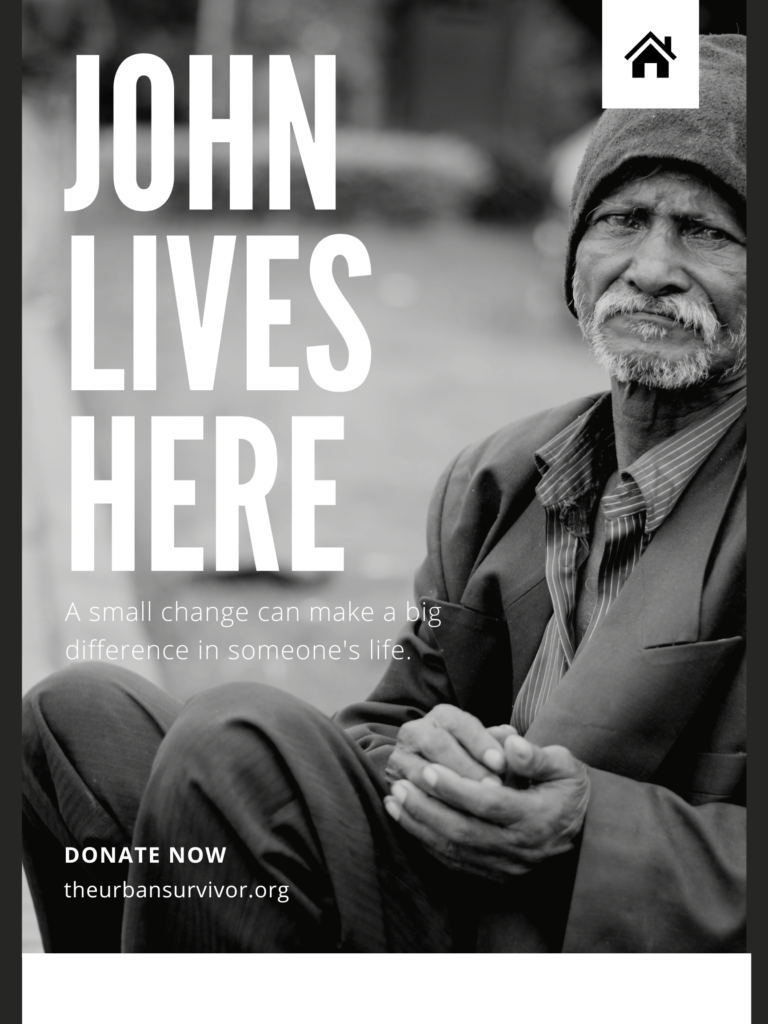

The prison and justice systems leave a lot of people homeless and undermine the housing stability of everyone who interacts with them. Prisons also compound problems with physical and mental health, addiction, and trauma (common risk factors for homelessness). Even short stays in prison can be enough to make someone lose their job and housing, making it a clear issue for the homelessness sector. As well, people who are homeless are disproportionately represented in prison—across Canada, over 16% of prisoners are homeless, up from 6% in 2009.

There are also major issues of social justice around prison that can only be addressed when we understand how people move through the system and what conditions they face. The awful conditions in provincial prisons amplify other forms of systemic oppression. For instance, it is nothing new to say that Black and Indigenous people are disproportionately represented among prisoners—but it feels different to say that Black and Indigenous people are more likely to be held in an overcrowded prison cell with no privacy or room to move around for weeks at a time.

The experiences of prisoners are not well understood within the homelessness sector, which can create barriers to accessing services. There are very few services available that specifically help people being discharged from prison, leaving them to seek out services that are not tailored to their needs.

By looking more closely at what prisoners go through inside the black box, we can work towards better outcomes for them and remove some of the added barriers they face to obtaining safe, stable, and affordable housing.

Originally Published @ Homeless Hub

October 11th, 2023

![The Canadian Penny [RIP] The Canadian Penny [RIP]](https://urbansurvivalmedia.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/si-220-penny-1936-7877445.jpg?w=210)